Gynaecological cancer is a group of eight cancers affecting the tissue and organs of the female reproductive system such as the cervix, vagina, vulva, ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus and endometrial tissue, peritoneal area, or other areas of the pelvis.

Because it affects so much of the female body, a woman in Australia has a 1 in 23 chance of developing this cancer by the age of 85. Australia has had a wide-reaching prevention program in place since the national cervical screening program was introduced in 1991. Within a few years, Australian researchers were instrumental in the development of a vaccine for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), which is responsible for the infection that causes cervical cancer. However, the screening program and HPV vaccine is not capable of preventing or catching all gynaecological cancers.

Here we look into some myths and misconceptions about the topic.

The cervical smear which is a more expansive test than the pap smear is only designed to screen for cervical cancers. The test collects cells from the cervix, which is the neck of the womb (uterus). There are no signs or symptoms in the precancerous and early stages of cervical cancer. Regular screening tests for cervical cancer every 5 years is required, and women are able to perform the test themselves under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

An updated HPV vaccine (also known by brand name Gardasil) was released in 2018, protecting both men and women against a greater spectrum of virus. It does not protect against cervical cancer 100%, so regular cervical cancer screening tests are still needed for those who have had the HPV vaccine.

Cervical cancer is caused by ‘high-risk’ types of HPV. There are more than 100 types of HPV identified and only a dozen or more types are considered high-risk for developing cervical cancer. In the majority of infections, the immune system will clear the virus within 12 months. However, if the body does not clear the infection and it becomes persistent, high-risk HPV types may develop into cervical cancer. A positive result requires monitoring including re-testing in 12 months.

Although gynaecological cancers do occur predominantly after menopause, it can also occur in young women. Women of all age groups should look out for the signs and symptoms of cancer and should not be complacent about their checks.

With removal of ovaries, the risk of developing ovarian cancer is much lower, but a small amount of risk (~2%) remains. As it is possible for the ovarian cells to migrate to other areas in the pelvis prior to removal of ovaries later becomes cancerous. Or if the ovaries were only partially removed.

A hysterectomy is a general term for the removal of the uterus, but there are different “ectomies” targeting different areas – the ovaries, fallopian tubes.

A total hysterectomy removes all of the uterus and cervix. It does not include

removal of ovaries. A sub-total hysterectomy removes the upper parts of the uterus – leaving the cervix intact. Removal of the ovaries is called an oophorectomy; with a unilateral oophorectomy removing one ovary, and a bilateral oophorectomy removing both ovaries.

Removal of the fallopian tubes is called salpingectomy and if the tubes are removed with the ovary this is called a salpingo-oophorectomy.

People get hysterectomies for many reasons, including treatment of fibroids,

endometriosis or adenomyosis; childbirth complications; cancer removal or

prevention; gender-affirming surgery; and other conditions. Cancer screening still needs to be done, as the cancer could have developed prior to removal, and microscopic parts of tissue which can re-generate may still remain in the body.

Ovarian cancer is difficult to detect early because the symptoms are vague, mistaken for other bowel, bladder or menstrual conditions and there is no screening test. While the majority of ovarian cancers are detected at stages three and four, it is possible to diagnose ovarian in its early stages. This is why it’s important to know the early warning signs. Women should present to a GP if they have a symptom which is new, persistent, unusual and different for them such as abdominal or pelvic pain, bloating, unexplained weight gain or loss, or fatigue.

While thrush is common in women, it usually will not cause persistent itching of the vulva. A biopsy of vulval skin and not a skin swab is required to exclude precancer and cancer.

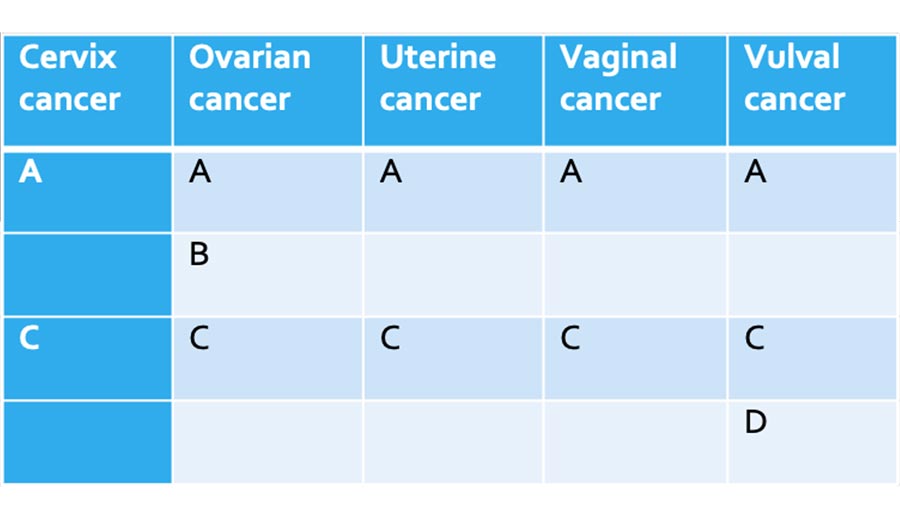

As this group of diseases affects a large group of organs and tissues, some of the symptoms can overlap between cancer types. We like to use the ABCDE model as a guide for identifying potential cancer.

A: ABNORMAL vaginal bleeding/discharge which may include

B: BLOATING feeling full quickly, indigestion, loss of appetite, weight loss or gain.

C: CHANGE in skin colour of vulva – red, pink, white, black.

D: DESIRE to itch/itching vulval skin

E: EXPERIENCING any of the above symptoms which is new and recurrent, or learn of a family link to gynaecological cancers, please see your GP and have a referral made to see a gynaecological oncologist.

For more information and risk assessment for gynaecological cancer refer https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au

Join me and my staff at any of the consulting locations in Brisbane.

P: 07 3841 5588

F: 07 3319 6926

E: drpsingh.reception@gmail.com

Level 2, Suite 299, St Andrews Place, 33 North St, Spring Hill QLD 4000, Australia

Level 1, Suite 6, 137 Flockton Street, Everton Park, QLD 4053

P: 07 3841 5588

F: 07 3319 6926

E: drpsingh.reception@gmail.com

Despite COVID-19 we are seeing patients who need specialist management. After initial consultation, the urgency (or category) of any surgery is assessed and booked based on the category.

Our practice offers prompt surgical bookings for category 1 and 2 patients. And wait-listing category 3 patients for surgery once current restrictions are lifted.